I spent a few sleepless nights wrestling with whether I should ask Tjarks to take a picture. I was on my way down to Texas to watch Game 3 of the Western Conference Finals between the Dallas Mavericks and the Golden State Warriors. I had a media credential for the game, but I really just wanted to see my friend.

Tjarks had come up to Chicago and crashed on my couch several times when we were both covering the McDonald’s All-American Game, but it had been a few years since I had seen him. A lot had changed since then: he married his wife Melissa, had his son Jackson, and he cut out the partying habits we indulged in during our 20s. Everything in Jon’s life seemed to be going great until he started feeling sick in early 2021.

I found out about Jon’s diagnosis on Twitter the same way everyone else did. He had an extremely rare form of cancer that was already in Stage IV by the time doctors identified it. I remember calling my dad, a family practice doctor, after reading Jon’s Tweet and hoping he could give me a reason for optimism. He couldn’t. Instead, he just said it wasn’t good and that he was sorry my friend was going through this. I am not someone who cries often, not even during “Titanic,” but I cried like a baby shortly after we hung up.

Jon and I talked on the phone a lot over the next few months, usually while he was in a hospital room waiting to go through chemo. On the first call we talked about his condition and how he was feeling, and caught up on what was going on in my life. But the conversation always turned back to basketball. We had bonded while covering the sport together when we both arrived at SB Nation as young sportswriters back in 2012. Somehow, we were lucky enough to still be doing it a decade later. Our talks would go from Giannis’ run through the 2021 playoffs to USC’s guards letting down Evan Mobley to Jon’s skepticism about Cade Cunningham’s NBA ceiling to whatever philosophical trend Tjarks thought was coming to the game next.

We almost never talked about his health. I would end our calls by telling him that I was praying for him and thinking of his family, but it never seemed like he wanted it go any further. Instead, the only updates I would get were the ones he’d begrudgingly give during his podcast appearances with Bill Simmons or J. Kyle Mann or Ethan Strauss. I knew that the brief spell of remission he had a couple months earlier was over, and that he was trying some experimental treatment that at least gave him a pathway to a somewhat normal life for a few more months.

When the Mavericks blew out the Phoenix Suns in Game 6 of their second round series, I decided I was booking a flight if the Mavs somehow pulled the upset in Game 7. The Mavs throttled Phoenix from the opening minutes of that next game, and I knew I had to get down to Texas.

We got dinner before the game, and I was a bit nervous heading into it. What do you say to someone you care about as they stare down the end of their life? Of course, Tjarks was as welcoming and comforting as ever. We talked a lot about Chet Holmgren that night, but never once about his fight with cancer.

Tjarks looked a little thinner and more pale than before, but everything else about our evening felt pretty normal. That’s why asking for a picture felt so strange. Taking a picture with a buddy should be a small gesture, but it was also just totally outside the normal scope of our friendship. I was worried about what it might signal if I brought it up: would he think I was looking for social media clout? Was the insinuation that I would post it after he died?

At some point around halftime, I asked him if I could send a selfie to my pals John and Kevin, wonderful basketball writers in their own right, who Tjarks knew from Twitter. “Of course,” he said. About an hour later, Andrew Wiggins posterized Luka Doncic, and the Warriors had gone up 3-0 in the series. I told Tjarks it was great to see him, and that he had to come up to Chicago again soon.

Tjarks showed up at my front door with a backpack and a bible. He gave me the bible and asked if I believed in God.

I was living in a house in Wicker Park with four of my closest friends at the time. Tjarks had crashed with us once before a couple years earlier for the 2014 McDonald’s All-American Game. I sat next to Jon at the practices with eyes on my Chicago boys Jahlil Okafor and Cliff Alexander, at the time two of the top-3 rated players in the class. It took Tjarks about five minutes to realize they wouldn’t cut it in the NBA. Instead, he was enamored with Karl-Anthony Towns and Myles Turner, bigs who could stretch the floor, and in Towns’ case, possessed some real passing chops, too. Tjarks loved nothing more than a big man with guard skills.

There was no bible in his hand during that first visit, but I could tell Jon was searching for something. He had been let go at SB Nation a couple months earlier. Essentially, I got a promotion that he wanted, and he didn’t have much interest in being at the company after that. I’m sure Jon was aware that he was a significantly better basketball thinker and superior writer than I would ever be, but he never held it against me. Instead, he gave me ideas for stories and inspired me to love the game as much as he did. After those practices, we’d stay up late in the night watching the NBA and talking about life. Jon knew his calling was to write about basketball, but at the moment he didn’t have an outlet for it.

Jon decided he was going to write a book on the 2014 NBA Draft called the “Pattern of Basketball,” and he later started a Blogspot with the same name. Free of having to work for anyone but himself, Tjarks’ writing soared. I remember these pieces criticizing Chris Paul and Steve Nash as standouts. Tjarks already had a good following when we worked together, but suddenly his stories were getting more attention than ever. To pay the bills, Jon picked up a job delivering beverages to stores around Dallas. It was around this time that he also decided to dedicate his life to Christianity.

By the time he made his trip to Chicago for the 2016 McDonald’s Game, he had just announced that he had accepted a job at The Ringer. I remember him telling me about the first time he talked to Bill Simmons and compared it to Kanye meeting Jay-Z. “I know you, but only from the TV.” The way he grinded to that opportunity by writing for no one but himself was so satisfying to watch.

To that point, I mostly considered Tjarks the guy who taught me about the benefits of the stretch four. Now he was in my apartment putting me on the spot for answers to life’s biggest questions. I mumbled my way through some awkward response about being raised Catholic, and thanked him for the bible, even if I didn’t have much interest in it. Then it was off to watch more hoops.

Some of the fondest memories of my career were Jon and I recording podcasts with my buddy Scott after those McDonald’s practices. We would watch a class that included Jayson Tatum, Bam Adebayo, Lonzo Ball, De’Aaron Fox, and Markelle Fultz go at each other in scrimmages, and then let our opinions fly at my kitchen table. I remember restarting the podcast several times because we were making each other laugh too hard to do a proper intro. I remember Jon pacing around the room carrying a baseball bat and doing check swings as we were recording, with Scott and I wildly gesturing for him to get closer to the mic. That was really peak Tjarks: he was never one for putting a slick coat on things, all he wanted was to say and hear an interesting take.

Tjarks played pickup with my friends and I during that stay, too. Jon was good enough to play AAU ball growing up. He told me about the moment he realized he didn’t have a future as a player — going up against Darrell Arthur in a tournament, and getting dunked on repeatedly. Fortunately for Jon, there were no Darrell Arthurs at my pickup run, which was mostly a mixture of nerds and stoners. Jon could still play: at 6’5”, he had an incredibly high feel for the game, and loved to facilitate out of the high post. I also found it highly entertaining that Tjarks had the most broke three-point shot imaginable, because he only liked prospects who could shoot. Sorry to rip your perimeter game now that you’re gone, my friend, but it’s true.

What I really remember about that pickup run was the way Jon pumped everyone up. I have always been a pretty trash basketball player: I’m short and slow with no left hand, and can only be described as “actively harmful” on the defensive end. That night, though, a few of my shots fell through the net. “Get some!” Tjarks yelled every time I hit a shot.

That phrase still comes out in the pickup run to this day every once in a while. I’m not sure anyone else remembers that Tjarks brought it into our lexicon, but I’ll never forget it.

Jonathan Tjarks was my favorite basketball writer. He saw the game so clearly, and somehow his writing style was even more coherent. The best writers are the ones who can convey big ideas using as few words as possible. That was Jon. I know that if I was the one dead of cancer right now, and he was writing a tribute to me, his story would half as long and twice as affecting.

For as great as Jon was at writing about basketball, the work he did writing about his mortality and his faith was even better. He published two incredible pieces at The Ringer: “The Long Night of the Soul” and “Does My Son Know You?” I will probably think about both for the rest of my life. On one of our calls, he told me this metaphor about driving off a cliff that hit me like a ton of bricks. Then there it was in his first of the two stories:

One of the best metaphors I’ve heard for modern life is that it’s a car headed toward a cliff’s edge while billboards line both sides of the road, blocking the driver’s view. Those billboards are all the distractions that society has to offer. Netflix. Sports. Movies. Music. Everything you consume to avoid thinking about where you are ultimately headed. And those billboards cover your view until the end of the road, when suddenly the cliff approaches. Then, as your car is flying in the air, that’s when you start thinking about death and the meaning of life.

As a Christian, I felt like I was prepared for that moment. But there’s nothing that can truly do that. It’s the long night of the soul. It’s a version of a well-known phrase that I often think of. I don’t care how strong your faith is. Staring into the abyss will make you question everything. I wish getting through it were as simple as quoting a few Bible verses and then going to bed.

For a while, I convinced myself Jon Tjarks would leave behind a bigger legacy in death than when he was alive. That’s how monumental his writing about cancer felt. Ultimately, I think that was just one of the stages of grief. I was certainly no stranger to bargaining, either. When his cancer was briefly in remission and he was back going to games and playing pickup, I prayed that he would make it 20 more years. Jon and I are the same age, both born in 1987, and making it to 55 seemed fair enough to me. Unfortunately, cancer drives a hard bargain.

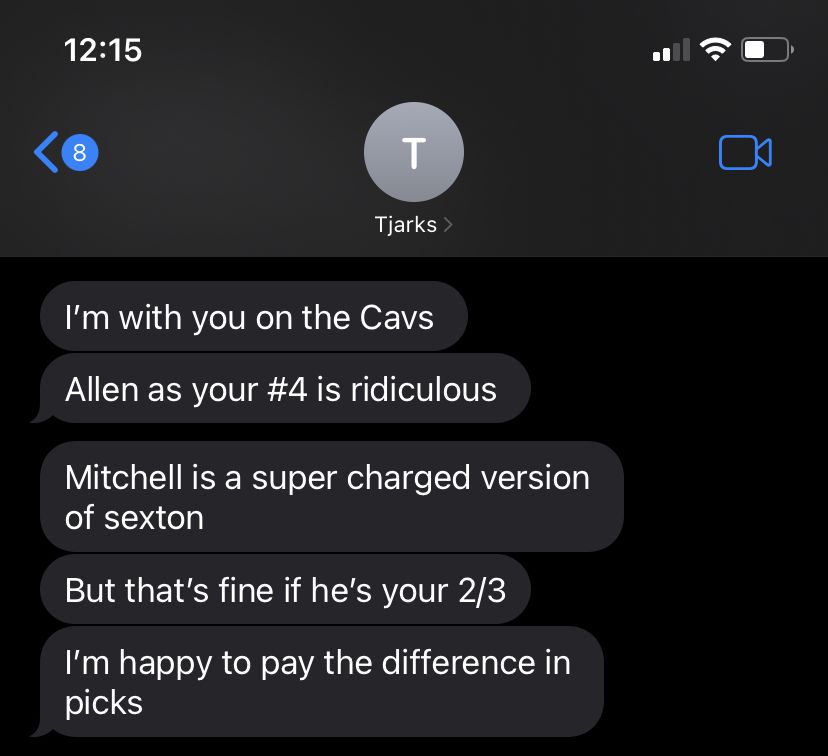

I arrived at acceptance while standing knee deep in the Pacific Ocean over Labor Day weekend. I had gone out to San Diego with my friends, and when I arrived I had a text from Jon. “What do you make of the Mitchell stuff?”

I told him I loved it for Cleveland. He hit me with his thoughts, too.

The next day, I got a text from Sean Highkin expressing dismay at the latest Tjarks update. I headed to Melissa’s blog, and my heart sunk.

Saturday Jon woke up with reduced feeling in his legs, and Sunday he woke up and couldn’t feel them at all. Monday evening his speech started slurring and we were very concerned. We went to the hospital from PT/OT rehab to get him checked out. They did a CT and ordered a stat MRI. At 3am Jon had the MRI of his brain and whole spine. It showed that a tumor that was teeny tiny two weeks ago is now compressing his cord again at T8. He is permanently paralyzed from the belly down. Another tumor is pressing on his hypoglossal nerve, which controls tongue movement, so half of his tongue is paralyzed. It’s really hard for him to swallow, and his speech is significantly slurred. Eating and talking take a ton of energy now. His tumors in his liver, skull, and elsewhere have grown significantly. One of our doctors said that he had only seen cancer grow this quickly once before. He’s been in practice for decades. What are the odds.

I sent Jon a couple more texts, but he never responded. A few days later, he had passed. Even while literally on his deathbed, Jon was still texting me about Donovan Mitchell’s fit on the Cavs. He still wanted to keep in touch. I can’t think of anything more Tjarks than that.

To my knowledge, this is the last interview Tjarks gave. His perspective about life was always so sharp, even in his final days.

These words of wisdom from Jonathan Tjarks last month (in an interview with @ChrisCarrino) on his perspective of life and the prospect of death were so moving and continue to stick with me. He knew what and who was important to him, and lived it with clarity and purpose pic.twitter.com/LFF9nMCZmE

— Kyle Boone (@Kyle__Boone) September 12, 2022

Tjarks loved Dallas the way I love Chicago. I fell in love with basketball by growing up with Michael Jordan — for him, it was Dirk Nowitzki. Jon’s first foray into writing came on internet message boards defending Dirk in his high school years. I know how rewarding that 2011 Mavs title was for him. Jon attended University of Texas and loved his Longhorns. His time there overlapped with Kevin Durant’s one-and-done season, and he was always a huge fan of KD. Tjarks also loved history and often found a way to weave it into his stories. He read more books than basically every writer I know. Jon also loved Jesus. His story about finding God while on Ecstasy at an EDM concert is a must-read.

It’s not that fair that Tjarks doesn’t get to continue watching and writing about Luka Doncic. His writing on Luka was always so good. I can’t believe I don’t get to pick his brain on 2023 No. 1 pick Victor Wembanyama, because it feels like he could be the personification of everything Tjarks wanted in a basketball player. Even in his final months, Tjarks was going on podcasts comparing Chet Holmgren to Kevin Garnett. Who else was doing that? Jon had such a unique way of seeing the game, and as Zach Lowe correctly noted in his phenomenal tribute to Jon on a recent podcast, Tjarks was also never concerned about being wrong.

This all pales in comparison to the fact that Jon won’t get to be around to see Jackson grow up. He loved talking about his boy so much over the last few years.

Jon is survived by Melissa and Jackson. Our friendship predates his marriage, and unfortunately I didn’t get to meet his family on my recent trip down to Dallas. In reflecting on Jon’s life and death over the last week, I kept being struck by how lucky he was to have Melissa by his side as he went through this. She is an amazing writer herself, and her updates over the last year meant so much to the people who cared about Jon. Thank God they both had their faith, too.

I’ve been thinking about that bible Jon gave me a lot lately. After he left town, I gave it to my mom, a preschool bible teacher herself, and she donated it. Someone out there, presumably in the southwest suburbs of Chicago, has a bible with Jonathan Tjarks’ name on the inside. I hope it means as much to them as it did to him.

Rest in peace, Jonathan Tjarks: a big man with a kind soul, a great writer and incredible thinker, a good friend to anyone who came into his life.

If you want to donate to the family of Jonathan Tjarks, here’s a GoFundMe page.